Leaving America Questionnaire #13

Janet Skeslien Charles, novelist, 14th arrondissement

What drives Americans to leave home and settle elsewhere? That question has been on my mind for many years. This series, Leaving America, seeks to uncover the multitude of reasons and lessons learned—beginning with Americans in Paris. Become a paid subscriber to access this newsletter’s archives!

Ps. Related this week: catch an interview with me ABOUT this series onSusanna Schrobsdorff’s excellent newsletters, It's Not Just You :

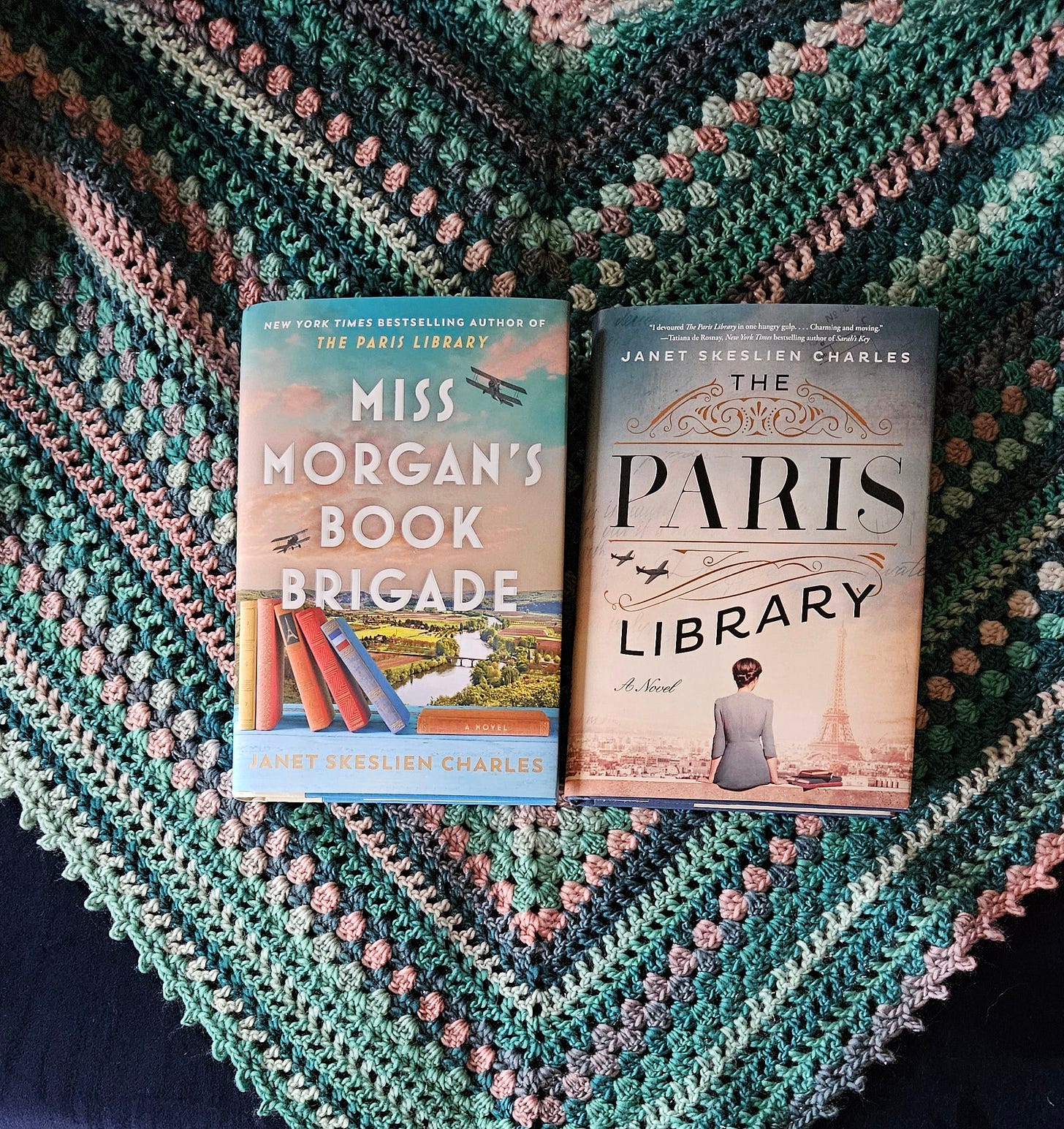

One way many Americans have landed in Paris, at least since the early 20th century, is through teaching. Janet Skeslien Charles was an English teacher and teaching assistant in France long before she became known as a bestselling novelist with titles such as The Paris Library, Miss Morgan’s Book Brigade, and her latest audiobook, The Paris Chapter. It hasn’t been an easy road, as she so honestly tells it below, but it has been rewarding and filled with community.

Where was the last place you lived in the U.S.?

I last lived in Missoula, where I took graduate classes and taught French 101 at the University of Montana. I’d just returned from Odesa, where I’d taught English at a local high school from 1994-1996. It was an incredible experience, and I missed my friends and the excitement of living there. As a full-time teacher in Ukraine, I’d made $25 a month. It wasn’t exactly a viable future, so I returned home to Montana. I was 26 years old and had no idea what I was doing with my life.

Did you intend to leave permanently or was the move temporary?

In 1998, I came to France for a school year. I’d applied to a French program for teaching assistants. (This program started in 1905 and is still open to people aged 20-35 today.) I was offered a job in Mulhouse, in Alsace. I booked a ticket to the local airport, but that flight was canceled because of an Air France strike. I was put on a plane to Charles de Gaulle Airport. That first day in Paris, I met Eddy, my future husband.

Was there a pivotal moment when you knew your life would be best pursued elsewhere?

In rural Montana, I always felt that my life was out there waiting for me. The things I wanted were different than the things that the people around me wanted. I wanted the big city, lots of choices, noise, and cultural activities. I wanted to travel and to speak foreign languages. Now that I’m older, I long for the quiet of the countryside; however, I could not have written my four novels if I had not moved abroad. As a writer, at heart, I am interested in journeys, the transitions we go through, the way that we react to change, whether it be marriage or divorce, a new job or getting fired, having children or not, breaking up with a friend, having cancer or Covid, or moving to a new country.

What sort of financial consideration did the move require, even if as a student initially? Does one need a plump savings account to make this work?

Back in Montana, a coworker and I were both accepted into the French teaching assistant program. He had a chronic health condition and decided not to take the job because he worried about medical costs. (If only we’d known that he would have had coverage through the job.) All this to say that I was fortunate not to have considered medical issues.

My monthly salary for twelve hours a week in Mulhouse was $750. To supplement this income, I gave private lessons.

A French student, a German teaching assistant, and I shared a small apartment with no living room, only a communal kitchen. It was well maintained; the landlords were a lovely retired couple. My roommates and I only had a landline phone. We didn’t have a television or a car. We rarely ate out. I grew up reading about Simone de Beauvoir, who lived in small hotel rooms in Paris, and Christopher Isherwood, who rented a room in a woman’s Berlin apartment. So with my living arrangement, I felt like I was following in their footsteps. It was a special year. I loved my roommates, students, and coworkers. We could take the bus or train to Germany or Switzerland for the day.

I moved to Paris in 1999 and got another job as a teaching assistant. It was a short-term work contract (CDD) instead of an open-ended one (CDI). When Eddy and I applied for apartments, my income was never considered, as if I didn’t even exist. It was frustrating.

To be a teacher in the French system, you must pass a difficult competitive exam, which includes translating from French to English and English to French. In 1999, exactly 6027 students signed up to take the exam, for only 1270 available positions. (The French keep excellent statistics.1) I didn’t think I could have passed, so I continued as an assistant rather than a teacher, and wrote stories about Odesa. This seems normal. Most creatives I know have two jobs. Tour guide and journalist. Website designer and editor. Writer and teacher. Bookseller and author. Thankfully, my superpower seems to be taking low-paying jobs and turning them into bestselling novels.

At what age did you leave? Looking back, was that too soon or too late?

I arrived in France when I was 27. It was a good age because I was still very optimistic and energetic. I’d had some work experience and had enough confidence in myself.

When did you know you'd made the right [or wrong] call?

When I realized I had married someone who understands how much work it takes to write. Long before I was published, he treated my writing like a full-time job, not some hobby. Second, when I met my writing group, I finally felt more at home in Paris. That made all the difference.

What does Paris offer you that your native home couldn’t and, perhaps, still can’t

Choices. There are so many choices. Maybe it is not so much a difference between America and France, but between rural and city.

A glass of champagne in a corner café.

People here can debate and still get along. I’ve seen my husband and brother-in-law have loud arguments one day, and the next, they are able to talk and joke.

As a writer, I pay attention to words. Here in France, you often hear the word solidaire. I appreciate how people come together here and have empathy for others. I’m sorry to say that in America, we do not often talk about “solidarity.” Unfortunately, many people didn’t have a problem with Trump until they were personally affected by his decrees. I am heartened by the recent protests.

Can you share any anecdotes about your highest and lowest moments in Paris?

Lowest professional moments: I had trouble getting a long-term job. Despite my best efforts, I remained a teaching assistant for seven long years. My coworkers viewed me as someone who would only be here for a few months, so they weren’t interested in getting to know me. Each year, I worked in three schools (often in different arrondissements) and gave countless private lessons. I spent more time below ground in the metro than above ground. Commuting and being on the run almost every hour of the workday was exhausting. I spent my spare time writing my novel and applying for jobs.

Since I was in my early thirties, French interviewers often asked about my plans for having a family. One even told me she wished I were “past the child-bearing years.” Finally, I landed an interview for the advertised role of Public Relations Coordinator at an American organization. During the meeting, I was informed that the position title had been changed to PR Assistant. I howled, “I cannot remain an assistant forever!” No surprise, I didn’t get the job.

Happy professional moments: When my first novel was published in the U.S. and UK, and when it was translated into French. I so enjoyed working with the editor and translator. The book won a few small literary prizes here and in England, and I was invited to several literary festivals in Paris, Bordeaux, Macon, Cognac, and even Tahiti. My husband and I did a literary tour de France. It was a great way to see the country.

This spring, I spoke at the Belleville library founded by Jessie Carson, the real-life heroine of my latest novel. In northern France during World War I, this NYPL librarian was hired by the American Committee for Devastated France to create libraries for families who’d lost their homes and livelihoods. At the time, books were the only form of entertainment or escape. After the war, Jessie transformed ambulances into bookmobiles. It is an incredible honor to share her story and to present my work at the library where she once stood.

Are there aspects of American life that you long for?

I’ve missed many milestones of loved ones, and wish I could have been there for them.

On a day-to-day basis, I miss moments of small talk, warmth, and connection with strangers. I miss the creativity and openness. In France, there is often only one perceived way to do something.

I also miss good customer service.

What book or movie do you most associate with the American experience abroad?

Lost in Translation with Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson. It conveys so well the feeling of being lost in life and feeling like you don’t understand. It also shows the tight friendships that form when you are out of your depth.

“There is so much that we do not control. We just have to do the best we can, with what we know, at any given time.” — Janet Skeslien Charles

If you had to narrow it down to one, what is the greatest lesson living abroad has taught you about yourself and the world?

Even though I speak French, I have struggled here, personally and professionally. I try to remind myself that we can take things easy or we can take them hard. We have to be patient with ourselves. So much comes down to chance. An Air France strike changed the trajectory of my life. There is so much that we do not control. We just have to do the best we can, with what we know, at any given time.

Have you ever considered going back? (Why or why not)