On Leaving America: A new series

Conversations about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness abroad

For the last eight years, I have thought at length about what it means to be an American citizen in the world today. I have thought endlessly about the moral value of kindness, decency, and generosity for the collective good—instilled in me from a young age—and its evident deficit. And I have considered the extent to which the nation has upheld its promise to protect the unalienable rights of its citizens. In other words, I have spent years thinking about the myth of American exceptionalism and the failure of past and present governments to provide Americans with a basic level of security, much less with the chance to pursue lives of meaning and connectedness.

The country, with its extreme violence, economic inequality, declining life expectancy, and fractured identity, shored up by systemic racism, is properly fractured. The ideological intensity in the United States has become nothing short of dogmatic. And the healthcare system, along with its inequities amplified by the pandemic, is in shambles.

From the perspective of foreigners and many Americans residing abroad, the idea of a shining city on the hill has long been recognized as an illusion. This was further reaffirmed in the last several years by events like the insurrection at the Capitol, the failed exit from Afghanistan, the devastating Dobbs decision on abortion, and last week’s election where disinformation, technological manipulation, and billionaire influence all but guarantee a dystopian, Project 2025-propelled future for the country.

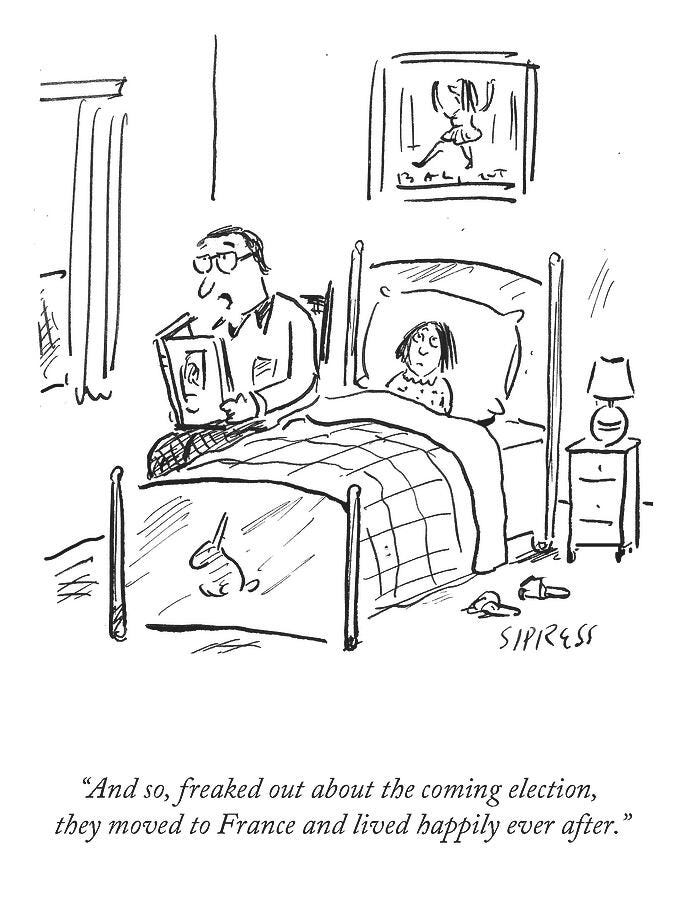

I wasn’t surprised to learn that Google searches for “how to move abroad” have soared since the election results were announced. Few will go through with it right away, if ever, but many will entertain the fantasy of pursuing a life elsewhere. I know some are morally opposed to the idea of fleeing when their nation is in crisis (or at least against the idea that leaving will fix *gestures wildly* all their problems), but let me point out that Americans have always done this, for various reasons.

This ongoing period of upheaval closely resembles the political and social turmoil of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s that prompted innumerable departures among the alienated, disenfranchised, or self-exiled. James Baldwin, among America’s most well known expatriates abroad, wrote that it was precisely his profound love for America that warranted perpetual scrutiny. It is for that reason that he would spend much of his life traveling, physically and psychologically, between the U.S., France, and Turkey, never finding home in his native land, never being able to forswear it.

When it comes to France’s pull on Americans, specifically, we can look straight to the Founding Fathers. Ever since Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were first seduced by France, returning home to reinforce a litany of ideas about the culture that remain prevalent today — a reverence for intellectualism and the arts; pleasure above all else— America’s oldest ally has occupied a distinct space in the collective imagination.

As I wrote in a piece for Mastermind a couple of years ago, by some accounts excelling (or ascending, depending on how you look at it) by way of France was the original American dream. Beginning in the post-Civil War years, American artists, among them painters, sculptors, architects and writers, were a particularly visible expat contingent in Paris. The art world was especially shaped by the migration of young Americans who enrolled in l’École des Beaux Arts and private academies in an effort to be at the center of Europe’s thriving artistic cradle. Intrigued both by the penniless bohemian and the insouciant flâneur, painters and writers alike in the late 19th and early 20th centuries set the foundation for an artistic character that would not only be depicted in their work but go on to instill generations of Americans with the belief in France as the home to creative emancipation.

That soft power continued well into the decades leading up to and following WWII, driving American performers, musicians, and writers, like Lost Generation matriarch Gertrude Stein, to build up their own vibrant cultural enclaves on Paris’s left bank and northern neighborhoods. But it was Josephine Baker, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin, the most iconic Americans in Europe, who pushed a narrative that established France as an indefatigable capital of liberty. Chased away from the States by racial segregation, they found not only creative recognition abroad but freedom from discrimination and the social injustices plaguing American society. France was a safe haven, “where the laws of segregation didn’t exist, where there was no lynching, where it’s possible to speak to a white woman without being threatened or killed,” says the French poet and writer Daniel Maximin. “Paris was a second New York, a Black and Caribbean capital where Anglophones, Francophones and Hispanophones came together in an incredible cultural effervescence.”

“It's called 'the American Dream' 'cause you have to be asleep to believe it.”

– George Carlin, 2005

As we have seen in more recent years, contemporary writers and thinkers share the sentiment. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s dispatches from his time in Paris with his family probed the age-old idea of leaving home to see oneself anew, although what he discovered mostly revealed what America wasn’t allowing him. “My body feels like it is my own and no longer performing for my tribe and its enemies. I perform for myself here. Because I have no tribe here (yet) and the blood feuds feel so very distant from me,” he wrote in the Atlantic in 2013. Being Black wasn’t the single most defining feature about him in Paris and that fact meant he could exist in a sort of freeing state of anonymity. “You play a lot of roles as a black man in America. But "Stranger" isn't one of them. You feel too marked—not even marked for ill treatment, but just marked.”

Why do people leave?

The constituency of Americans abroad (5.5 million by some estimates) is often overlooked or reduced to the stereotype of a cohort of privileged expatriates who make limited attempts at assimilation. Not only is this an incorrect assumption but it carelessly disregards the very real and varied reasons a person might elect to leave home. What’s more, the story about American migration focuses almost entirely on pull factors—the reasons immigrant populations have been drawn to the United States—rather than the push factors, or conditions driving Americans to leave their own country and stay away.

I left the United States at age 20, long before I was thinking philosophically and critically about where I was from and what leaving meant for my life. I didn’t flee to France due to war, persecution, or discrimination, but I quickly met people in Paris and throughout my travels who had. The reasons I stay, beyond the fact that it feels, ineffably, like it was always my true home, are legion. Affordable healthcare, access to culture, and quality food, on top of quality of life overall, certainly top the list and those realities became even more vital as I struggled to manage my Tourette Syndrome in my thirties.

While political and societal polarization may be reigniting the dream of starting over for some, for others it’s economic fallout, existential listlessness at home, or a life’s-too-short wake-up call fueled by the pandemic, personal loss, or life-threatening events that motivated them to reevaluate their lives. Rarely are these Departures in the grand, uppercase sense of the word, where the decision to go can’t be reversed. But they are consequential in how they transform an individual and the way they see the world.

Several months into the pandemic, I started threading some of these thoughts into a project that would examine the multitude of often overlapping and complex reasons one might leave and how doing so could be transformative. I had imagined the project as an anthology of essays and stories by and about Americans scattered across the world in more than 160 countries. Publishers, sadly, had other ideas.

So I’m bringing this project to you here, now, in a slightly different form than initially imagined, because I’m still thinking about these things. Twice a month, I’ll publish a questionnaire (à la Oldster) with an American who has settled in Paris. The first will land in your inboxes this weekend! From there, and if you’re enjoying them, I hope to extend it to Americans living elsewhere in France before taking it global.

And a final thought

No matter how imperfect governance and daily life may be in France, or any number of countries Americans have adopted as their homes, the idea of fashioning an alternative trajectory, far from the grip of the American myth, has never been more compelling to those open to the possibility of change. Even if you never intend to leave home, I hope you will find something inspiring or compelling in each of the conversations.

Thanks for reading! If you think a friend would enjoy The New Paris Dispatch or this series, gift subscriptions are available here | Order copies of my books The New Paris and The New Parisienne.

*Custom header design by Samantha Dion Baker

Impressive writing. I think you captured well the complexity of our American way and the role that others perceive or exult in. And the struggles many people feel about our imperfect union.

Fleeing to Paris in the footsteps of Baldwin, Baker and Simone resonated so much to me when I escaped in 2017 and it pains me to see that the US is once again entering another dark chapter where marginalised citizens are leaving to ensure they can continue to live in the body they occupy. Thank you for making space to honour these experiences and to share them with the world. I can't wait to hear them.