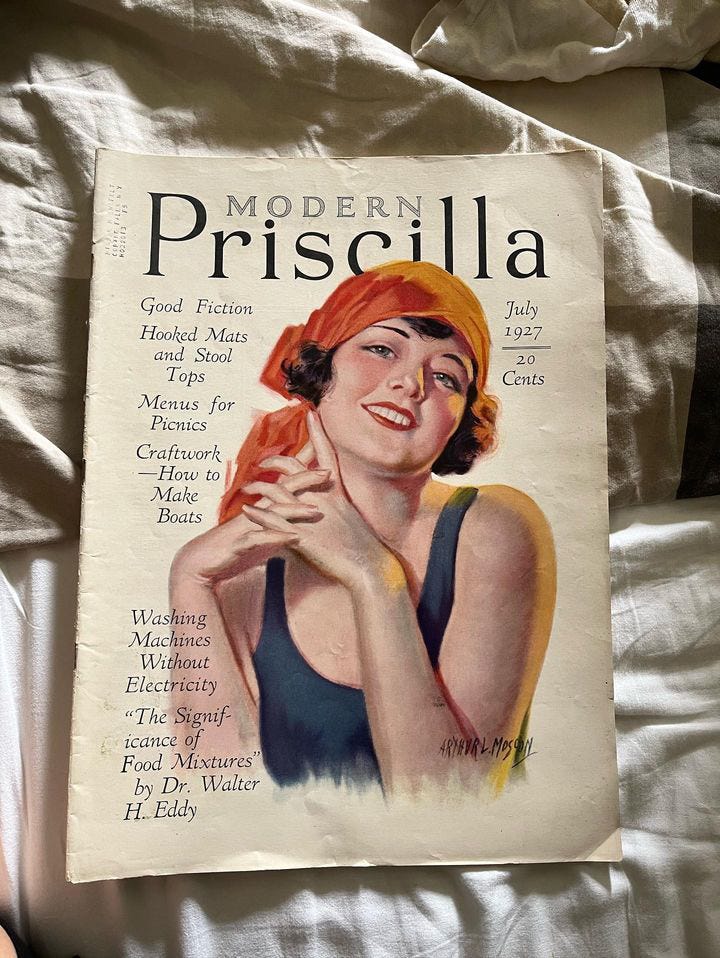

From the Archives: French Supremacy

Storytelling through women's magazines of years past

Whenever I’ve spoken in public about the myth of the Parisienne since The New Parisienne was released, my favorite moment has been seeing a flicker of astonishment in the eyes of those listening when they realize how far back its creation goes. A light bulb goes off and the mental wheels start turning wildly.

In the book I speak about Jean-Jacques Rouss…